I am a Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading (UoR). I completed my PhD in political science at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa in 2023. I previously worked as a researcher at Afrobarometer, a leading pan-African research institution, as well as a Guest Teacher at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Governance and Local Development (GLD) Institute at the University of Gothenburg.

I study Comparative Politics and Political Behavior, focusing on Africa. Using quantitative and qualitative approaches, my research focuses on how political institutions enhance democratic accountability and facilitate human development. Specifically, I am interested in the internal organisation of political parties as well as legislatures, and how their representatives affect processes of democratisation and development. In a related line of inquiry, I focus on how governments, political parties, and citizens deal with the challenge of climate change. This research has been supported by the Institute for Democracy, Citizenship and Public Policy in Africa (IDCPPA) at UCT and the GLD.

A second stream of research assesses judicial power in Africa and its implications for citizens’ perception of the courts on the one hand, and the quality of elections on the other. Parts of this research have been supported by the Norwegian Embassy and the Social Justice Initiative via the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit at UCT.

My research has been published or is forthcoming in Comparative Political Studies, Democratization, Journal of Southern African Studies, Nature Climate Change, Party Politics, and Public Opinion Quarterly, among others.

Edited Volume (in progress)

The New Ground Wars: Changing Ground Campaigns in Africa, co-editing with Dan Paget and Sarah J Lockwood.

In much of Africa today, ground campaigns, simply put, are big. The rates at which political parties and activists of all kinds reach people on the street or the doorstep are similar to those of the most vigorous ground campaigns in the Global North. Given their scale and vibrancy they are, more than ground campaigns in other places and times, the fields on which elections are won and lost. They are fronts on which authoritarian rule is defended and assailed.

In spite of the vibrancy and importance of these ground campaigns, and for all that past research has uncovered, there is much which we still do not know about them. In this volume, we seek to assemble a series of cutting-edge contributions which in different ways, begin with this question: how is ground campaigning in Africa conducted today?

We hope to assemble a set of theoretically and empirically original contributions that tackle this, and one of the related question, including: what are the modes of contact; who is targeted; what meanings are made; how are campaigns organized; how do ground campaigns fit together; and what is the impact of campaigning on election outcomes and citizen attitudes and behaviour.

Photo: Sarah J Lockwood

.

Most Recent Work

African Governments are Primarily Responsible for Climate Action, According to Their Citizens, with Talbot M. Andrews, Nicholas P. Simpson, Andreas L.S. Meyer, Christopher H. Trisos, and Debra Roberts, 2025, Communications Earth & Environment.

Abstract: Global increase in the pace of climate action is urgent. Yet, it is less clear who citizens expect to take the lead on climate action across different regions of the world: historical emitters, their own governments, or themselves? Our analysis of Africa’s largest public opinion survey, the Afrobarometer, across 39 countries finds that Africans place primary responsibility for addressing climate change on their own government, a further third see ordinary citizens as most responsible, while very few place responsibility on historical emitters. Multinomial logistic regression analysis shows that education, decreased poverty, and access to new media sources are associated with increased attribution of responsibility to historical emitters. Our results suggest that poverty alleviation and increased access to education, combined with professional frontline government bureaucracies can re-apportion citizen expectations of responsibility for climate action onto historical emitters and actors with more resources for scalable climate action.

African Legislators: Unrepresentative Power Elites?, with Robert Mattes and Shaheen Mozaffar, 2024, Journal of Southern African Studies.

Abstract

African legislators both resemble and differ from the societies they claim to represent in important ways. Based on a unique survey of representative samples of parliamentarians in 17 countries, we find that legislatures are representative of national publics in terms of ethnicity and religion. At the same time, compared to ordinary African citizens, their MPs possess far higher levels of education, and are far more likely to be older, male, and come from professional or business backgrounds. Besides coming from higher social and economic status backgrounds, many MPs also previously held senior posts in the state and national government, or leadership positions in their political party. Does this mean that African legislators constitute a coherent, self-interested, social, economic and political ‘power elite’ detached from the interests of the voters? In the legislatures under investigation, we find little evidence of this effect. Markers of social, economic or political privilege and power overlap irregularly and in a non-cumulative way. Thus, far from comprising a slowly changing, cohesive and self-interested elite, Africa’s legislators come from a plurality of social and political backgrounds, and are relative legislative neophytes.

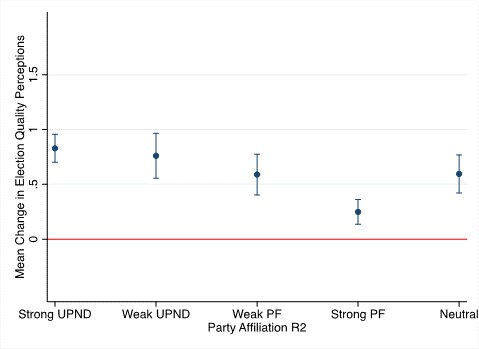

Where are the Sore Losers? Electoral Authoritarianism, Incumbent Defeat, and Electoral Trust in Zambia’s 2021 Election, , with Nicholas Kerr and Michael Wahman, 2024, Public Opinion Quarterly.

Abstract

How do electoral turnovers shape citizen perceptions of election quality in competitive authoritarian regimes? In this paper, we argue that electoral outcomes are crucial for determining perceptions of electoral quality. While detailed evaluation of electoral trust is complex in competitive autocracies with institutional uncertainty and polarized electoral environments, turnovers send strong and unequivocal signals about election quality. Previous literature has noted a strong partisan divide in electoral trust in competitive authoritarian regimes, but turnovers can boost trust among both incumbent and opposition supporters. We test this argument in the case of Zambia’s 2021 election, a case where a ruling party lost an election despite electoral manipulation and strong control over the Election Management Body. Using data from the first-ever panel survey carried out during Zambian elections, we compare trust in elections before and after the election. We find that perceived election quality increased after the 2021 electoral turnover among both losers and winners. Trust in elections increased the most among winning opposition supporters. Moreover, despite the outgoing president’s attempt to portray the election as fraudulent, losing ruling-party supporters also increased their trust in elections after the turnover. The study has important implications for the literature on democratic consolidation and institutional trust.

Most Recent Afrobarometer Publications

Africa’s Digital Divide Is Closing, But Participation In The Digital(ised) Economy Remains Highly Uneven, with Shannon van Wyk-Khosa and Rosevitha Ndumbu, 2025, Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 95. English .

Was South Africa’s 2024 Election a win for Democracy?, with Rorisang Lekalake, 2025, Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 991. English .

Whom Do African Election Campaigns Contact? And Does It Matter?, with Robert Mattes and Sarah Lockwood, 2025, Afrobarometer Working Paper No. 208. Pre-Print.